Mark 1 Coaches

A trip this weekend on the Gloucestershire Warwickshire Railway rather unexpectedly turned up some splendid mid-20th Century interiors. Not being up on my trains I had to do some research and found out these are Mark 1 coaches built between 1951 and 1963. They were intended as ...

Shatwell Farm Barn

I visited an intriguing building this week at Shatwell Farm near Castle Cary in Somerset. Its a cow shed but one with rather higher ambition than your typical farm building. Designed by Stephen Taylor Architects the barn is part of a cluster of agricultural buildings in a small valley at the edge of the Hadspen Estate. The owner has carried out a ...

Cadaques

I spent last week in Cadaques, a coastal town in north-east of Catalunya. I was struck by how well some of the new houses on the outskirts of town have been built into the natural landscape.

Once a sleepy village, Cadaques was made popular as a tourist destination by its seclusion from the crowds on the Costa Brava and associations with artists of the Modern era such as Marcel Duchamp and Salvador Dali. Since the 1950s the original whitewashed fishing village has been expanding out of its little bay over the surrounding hillsides. The town is hemmed in by the Cap de Creus national park on one side and the sea on the other so there is immense development pressure on any available parcel of land. Most of the buildings in the old town are painted white but recent new developments on the periphery use the local stone. I don’t know the planning policy but it looks like it has been decided that beyond a certain limit new buildings would have to be clad in stone to preserve the visual clarity of the original nucleus of the town. The policy wasn’t to stop development but rather to impose a kind of school uniform that all the individually designed houses have to wear that gives maintains a sense of place.

The hills behind Cadaques have been terraced with dry stone walls and planted with olive trees for centuries. In many of the new developments stone walls form terraced gardens on the steep slopes and I noticed quite a few where the terraces merge into the walls of houses. The houses are all concrete framed and the stone is just cladding but the homogenous material blurs the distinction between the buildings and the natural forms and colours of the hillside.

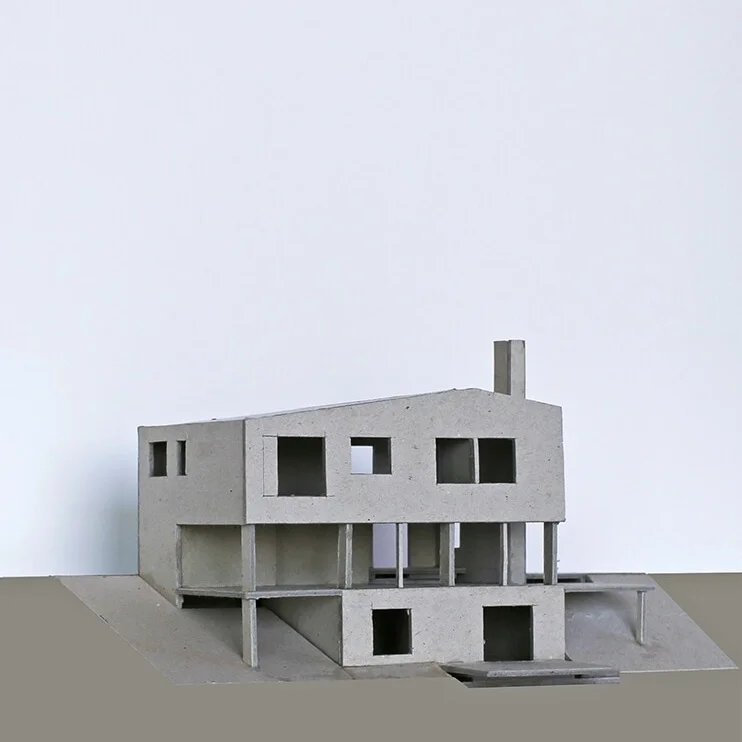

The gardens of the houses around where we stayed were planted with indigenous species, particularly Mediterranean stone pines (pinus pinea) that go some way to absorbing the houses into the landscape. It helps that all new buildings in Catalunya have to be drawn up by an architect so there is plenty of invention within the restrictions. The house below reminded me of our Newington Green House:

MORE POSTS:

Venice Biennale British Pavilion

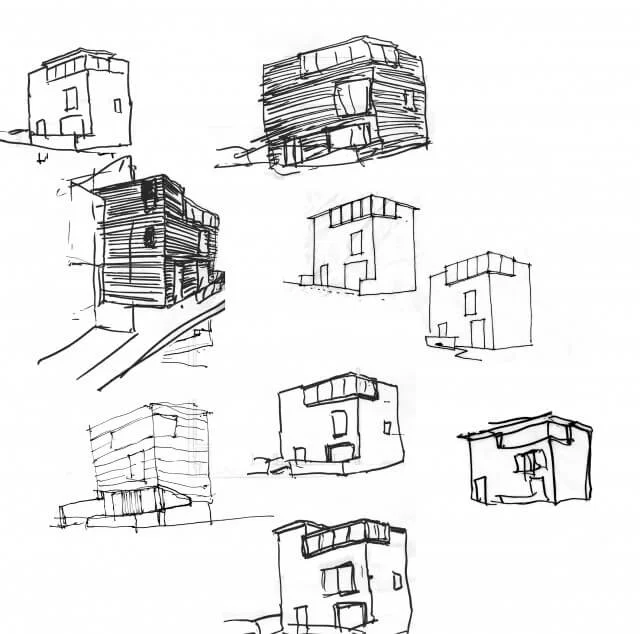

In June I submitted an exhibition proposal for the British pavilion at the 14th International Architecture Venice Biennale. The title of the 2014 Biennale is “Fundamentals” and overall Director Rem Koolhaas has called on national pavilions to respond to the theme “Absorbing Modernity: 1914-2014”. The competition to curate the British pavilion is being run by the British Council.

The brief called for a historical perspective on the past 100 years and crucially used the word Modernity with a ‘y’ rather than Modernism. The story of Modernist architecture in the British context has been well told and it is predominantly a history of an urban elite imposing artistic ideas imported from abroad on a largely unappreciative public. The interesting thing to me about the theme was the opportunity to look at Modernity not from the point of view of style but from its practical application by the wider population. This idea resonated with attempts I had been making to understand my new situation as a county dweller and as an architect how I should respond to the rural environment. A relationship to the natural landscape is accepted as a core part of the British consciousness. A theme began to emerge of how has this sensibility has been challenged by modernity and how the landscape has been adapted to the needs of a changing society.

A primary ambition of Modernism was to bring people closer to nature in a reorganised industrial society away from the pollution and disease of the traditional city. Through the re-colonisation of the countryside, new practices developed, and mass communication has increasingly enabled non-urban dwellers equal access to the global discourse. Agriculture, the armed forces and industry, all drivers of technological progress make use of the space, resources and development opportunities in the countryside. As such, far from being parochial backwaters, many rural areas have been laboratories of Modernity.

Building in the city is a self-conscious affair where context, precedent and often challenging briefs have to be intricately woven into an architectural whole to the satisfaction of strict planning authorities. In rural areas there was a much more laissez-faire attitude through much of the 20th Century and most built-structures from the period were erected without troubling an architect. Perhaps steel barns, concrete missile silos and pre-fab houses could tell a parallel story of Modern development determined by need, practicality and economy.

above: Steel hay barn, Somerset

above: Military installations at Orford Ness, Suffolk

above: Bridge over the M3 at Fleet Services

I submitted the proposal, entitled “Landscapes of Modernity” in collaboration with Rob Gregory, Programme Manager at the Bristol Architecture Centre. Some of the questions we raised include:

– What characterises the British landscape?

– How has its identity changed during the period 1914-2014?

– Does a conflict exist between those seeking to protect their notion of a rural idyll and those embracing modernity?

– Is the vernacular a relevant concept in architecture today?

– What is the role of nature in a country where much of the landscape is man-made?

– Why are traditional or historic features of the rural landscape more valued than modern equivalents?

– What is the appeal of functional buildings?

– Does romanticising the past or picturesque structures help or hinder the search for solutions to present-day problems such as housing provision and infrastructure?

– How has government policy affected development in rural areas during the period?

– What has been the role of planning authorities in shaping development?

Ours was one of 4 proposals short-listed and we attended an interview but we did not win. I was rather looking forward to spending the next year researching the subject and decided to start this blog as a place to gather information on rural architecture, landscape and the identity of the countryside. I hope it might also become a forum for discussion of these issues and I welcome your comments.

MORE POSTS:

Barn 1

At the bottom of the field in front of my house is this shabby Dutch barn. Most people’s reaction is ‘I bet you wish that barn wasn’t there’, but I actually rather like it. It is prominent but doesn’t block the view. There aren’t many buildings I’d be happy to see there but this utilitarian shed represents something about why I moved to the country and how man and nature co-exist in the English landscape.

Homes for Heroes

Finding the right rural building plot isn’t easy. You (quite rightly) aren’t allowed to build on open countryside outside a village curtilage as defined in the Local Development Framework. Unless you are a major house builder the only options are to divide up a larger plot within a village, to convert an agricultural building or to buy a house and knock it down. The plot we found had a ramshackle bungalow on it whose owner had recently died having lived in it for 40 years. Its location is idyllic, just within sight of the next building at the edge of a village with a fantastic view to the south across the Somerset Levels.

Our intention was always to demolish the bungalow and start again – after all, building a new house was the deal that had lured me out of London. But there was something about the simplicity of the little place, 4 rooms around a central hallway-cum-sitting room, and the fact that someone had lived here happily for so long with a minimum of modern comforts that made us rather sentimental about it. It had no pretentions, just the quiet dignity of something built efficiently and economically to fulfill its purpose.

I don’t have any information on the original design – does anyone out there know more about it? Perhaps it was never intended to last long. There’s no reason a timber frame won’t last for centuries if kept dry but with only a small fireplace to dry out the damp and less than adequate maintenance ours was suffering seriously from rot. A pipe had burst, soaking the inside and by the time we started work there were mushrooms growing on the floor. There was no alternative but to start again. We salvaged what materials we could but most of the timber was rotten and the walls were lined with asbestos boards. All we have are the thin softwood floorboards which so far have only been used to make compost bins.

We had looked at a few sites that had similar bungalows on them, all being sold as building plots, and we’ve found several more not far away. Ours was built around 1920. It had a softwood timber frame with painted softwood cladding and an asbestos shingle roof. After the 1st World War the shortage of labour and orthodox building materials led to the government offering subsidies to local authorities for houses built using non-traditional methods that could take advantage of the spare production capacity from the armaments factories. Systems were developed using concrete, steel, cast iron and timber and around 50000 were built in the decade following the 1st World War.

And now people like us are pulling them down. Maybe its inevitable but it is rather sad that a whole typology is slowly being removed from the landscape. Part of their appeal is their small size and lack of permanence – ours certainly had something of the frontier about it. A flimsy timber system-built house is the antithesis of the Englishman’s house as his castle. We liked the way the well-kept garden had grown around it so that the fruit trees were of a similar scale to the bungalow, preventing it from dominating the site.

Here are a few photos of ours taken in the autumn sunlight the first day we went to see it in 2010. If you want to stay in a similar house there is a 1920s Boulton & Paul bungalow in north Devon you can rent owned by the Landmark Trust.

MORE POSTS:

The Stones of Tuscany

Most of the cities are built from brick with stone reserved for the grander public buildings. The use of a dark and light marble in horizontal bands gives the churches such a bold presence, the clean-cut white stone making crisp shadows in the strong sunlight. The pattern is forgiving of crude repairs and the patched surfaces record the passing of the centuries.

Metalwork

This morning I went to see the progress on some of the metalwork for our house. I love the fineness of metalwork, the crisp lines and economy of material, and the way it can bear the marks of how it was made. We’re using steel for a number of internal and external elements to provide a contrast with the chunkier oak structure and linings. Two metalworkers are making things for the house as there’s quite a lot of it and everyone seems to be busy despite the recession. These photos were taken atCastle Welding.

Long Sutton Passivhauses

Welcome

Hello, and welcome to our Journal. I am Graham, one half of Prewett Bizley Architects, living in Compton Dundon, a small village in Somerset. I moved here with my wife Emily, an interior designer in 2011 having lived in London for 15 years. We had our son Arlo two weeks after we arrived but he was only one of two major projects that have dominated the first two years. The other was building our own house on a beautiful south-facing slope just above the Somerset levels. We bought the site at auction in 2010 and had obtained planning permission by the time we moved. So my first 8 months in Somerset were spent doing the detailed design for the house, changing nappies, and trying to get some sleep myself occasionally. Work started on site in January 2012 and we moved in at the start of November the same year. The house has been built to Passivhaus standard which means it has extremely high levels of insulation and air-tightness. It wasn’t finished of course but at least we were in and we have been carrying on with the work in a slowly decreasing state of chaos around our day jobs.

In the Journal I will be talking about architecture, low-energy construction, and urban design. Primarily though I want to explore aspects of rural architecture and planning. Being a new arrival in the country I am conscious of bringing with me the attitudes of an urbanite, one of them Londoners. I am keen to explore issues that determine how development occurs outside of urban areas, to develop an approach for how to design in the countryside and to understand better where I am.

Please get in touch or leave a comment. I’d love to hear from you!